PORTRAITS IN VICTORIAN STAINED GLASS

Jim Cheshire

Q & A with Dr Jim Cheshire (University of Lincoln)

December 2020

The inclusion of portraits in stained glass is not new, and donor portraits were common in the medieval period. But as Dr Jim Cheshire (Lecturer at University of Lincoln) argued in a recent talk on 'Portraiture in Victorian Stained Glass', delivered as part of The Stained Glass Museum's 2020 online webinar series, from the 1860s onwards this became much more common in stained glass reaching a peak in the period following the First World War.

Our Director of The Stained Glass Museum, Jasmine Allen (JA), caught up with Jim Cheshire (JC) after the webinar to continue the conversation, and ask some additional questions raised by attendees at the online webinar.

PRECEDENTS & CONTEXTS

JA: There are many figures within medieval and Renaissance stained glass windows that might be considered ‘portraits’. But did pre-photography era portraits in stained glass (those known and unidentified) use portraits in a different way?

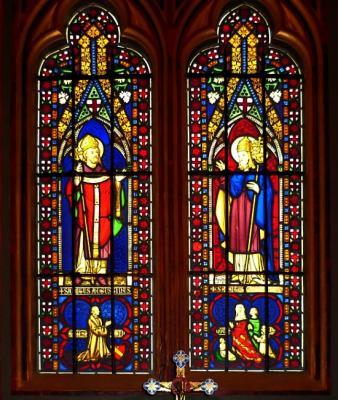

JC: Yes pre-Victorian donor figures are portraits and some Victorian examples follow this precedent closely (i.e.Pugin’s donor figures of his family in the Chapel at the Grange, Ramsgate, 1844). But from the 1860s portraits increase in scale and in the way are they integrated with iconography, rather than being external, figures were merged into the imagery in unprecedented ways.

Pugin's Donor Figures at the Grange, Ramsgate, 1844

JA: If we have lost the identity of the sitter, what is the significance of the portrait in a stained glass window?

JC: In this context, the status of the portrait becomes ambiguous. In earlier periods, as only powerful people commissioned portraits their anonymity was unlikely but as portraits became increasingly cheaper, sitters became less prominent. The result is thousands of anonymous cartes-de-visites which we can longer connect to individuals – a symptom of the modernity of the new medium of photography.

JA :So is the portrait a category or type of stained glass advertised and made available to the consumer?

JC: I am not convinced that portraits became types, as the subjects were designed to be identifiable. In fact, they could be defined as different from the stock types of saints and figures reproduced by stained glass studios.

Victorian photography examples

REMEDIATIONS

JA: You mentioned that when portraits are copied from photographic or printed sources, the glass painter often made a signature change, adding or removing an attribute or changing a pose or item of clothing. Were there any practical concerns over copyright or accusations of plagiarism in adapting such images for stained glass?

JC: I have not come across any such concerns, the point here is that remediation is never seamless: a trace of the process also remains.

JA: Can we distinguish between portraits as ‘types’ (e.g. used for modelling religious figures) and portraits as ‘accurate representations’ for commemorative or memorialising purposes, or are these distinctions sometimes blurred?

JC: I think we can make this distinction, but it really depends on the knowledge or awareness of the viewer. We might compare this with knowing that Fanny Cornforth or Elizabeth Siddall was the model for a given Pre-Raphaelite painting, despite this not being the intention of the artist.

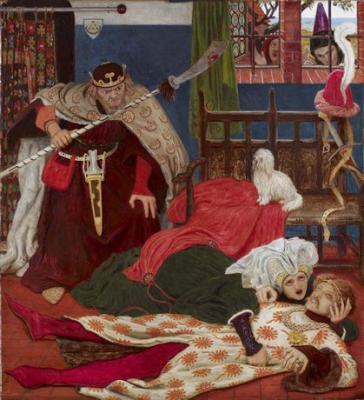

JA: Was an image in stained glass ever adapted for a painting, or was the influence always the other direction, e.g. painting adapted for stained glass?

JC: Ford Madox Brown’s Death of Sir Tristram (1864) in Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery originated as a stained-glass design for Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co and then used as the basis for a watercolour and an oil painting.

Death of Sir Tristram by Ford Maddox Brown, 1864

JA: Stained glass is most often employed as an architectural decoration within a building, so a portrait in a large stained glass window is seen and presented in a different context to a portrait represented in an oil painting or sculpture. How does this change how we should view these works?

JC: This is a complex subject as it depends on what the building is used for. It is an area that needs more research but I think portraiture being integrated into religious or civic imagery has implications for how audiences perceive the religious or social status of the sitter.

FAITH & MEMORY

JA: Portraits that represented individuals in memorial windows provided a way of remembering the dead, but within an ecclesiastical context were also demonstrations of faith - and belief in the afterlife. These themes sparked a number of questions from attendees at the webinar...

Attendee: Where portraits appear within religious windows, and especially when portraits of individuals were incorporated into biblical scenes, was there ever any discussion over whether this was appropriate? Sometimes figures are side-by-side with Christ, or even appear amongst an angelic host? What does this tell us about Victorian religion, faith and mourning?

JC: I have never come across this but I would love to find examples. As those depicted were often patrons, I think potential critics hesitated to publicly criticise them but I think many people must have found this objectionable.

Attendee: Is there a difference between portrait representations of deceased individuals, and those still living? I noticed in some windows those who were dead (shown as Jairus’ daughter for example) appeared to be depicted in less colour than the other figures and wondered if this was significant?

JC: This is really interesting and I had not thought of that distinction. I don’t think this is always true and I think the place of the portrait within the window was largely the result of a negotiation between the patron and the stained-glass studio.

Attendee: I wonder who would see these images, and whether individuals would be recognised within windows in parish churches, at least when in living memory?

JC: I think individuals must have been recognised on a parochial level and part of me suspects this was part of their intention. Just as power in a rural parish was often monopolised by one or two individuals (often described as a ‘closed’ parish), I suspect these individuals also sought to exert their moral power through means such as this.

Readers may be interested to read an article by Jim Cheshire published in the online journal 19 (Issue 30, 2020) on Remediation, Medievalism, and Empire in T. W. Camm’s ‘Jubilee of the Nations’ Window at Great Malvern Priory which discusses the transfer of visual imagery from photography to oil paintings and glass painting.

NEWS

WHAT'S ON

Opening hours

Summer (1 April – 31 October)

Monday -Saturday 10:00am – 5:00pm (last admission 4:30pm)

Winter (2 November – 31 March)

Monday -Saturday 10:00am – 4:00pm (last admission 3:30pm)

Monday -Saturday 10:00am – 5:00pm (last admission 4:30pm)

Winter (2 November – 31 March)

Monday -Saturday 10:00am – 4:00pm (last admission 3:30pm)

Donate

The Stained Glass Museum is an independent accredited museum and registered charity no. 1169842.

Donate

Donate